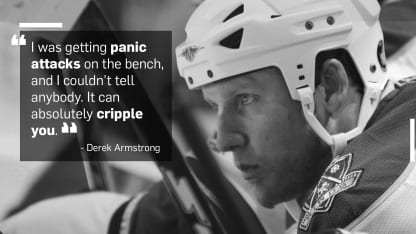

Armstrong, who was drafted 128th overall in 1992, was forced to walk away from hockey after playing professionally for 17 years when he incurred several serious concussions.

Like many, if not all professional athletes, Armstrong struggled to adapt to life outside the rink and felt the absence of structure and friendships that came with being part of a team.

"They say athletes die twice. You die when you leave the sport, and then you die when you die," said Armstrong. "I firmly believe that."

The adjustment from the rink to reality was not only a physical transition, but a mental one as well. Armstrong has been open about his own mental health struggles, which included anxiety and depression.

"I've always been a free-spirited guy and always happy, and I couldn't believe that those kinds of emotions could actually surface," said Armstrong.

While battling with these internal demons, Armstrong still had to put on a brave face for his wife and two kids, who are now 15 and 18. He was adjusting to being at home full-time, while still balancing the responsibilities of being a husband and a parent.

Four or five years ago he didn't think he'd ever feel like himself again.